Made in Palestine, a historic exhibition of Palestinian art was curated and exhibited at the Station Museum in Houston Tx in 2003.

The show was expected to travel but was turned down by more than 90 venues. In 2005 The Justice in Palestine Coalition which included Break the Silence Mural Project, Middle East Children's Alliance, Queers Undermining Israeli Terrorism, the Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee and many others, in collaboration with the Station Museum, brought the show to San Francisco.

It was a great success with more than 1,500 people attending the opening and closing events. Each evening there was an event sponsored by a local activist group building and strengthening relationships across movements. The show then went on to NYC, Mexico City and Montpelier VT.

Made in Palestine SF Program Events

Introduction by James Harithas, Director, Station Museum

The exhibition Made in Palestine chronicles the modern history of the Palestinian people from Al Nakba (the Catastrophe of l948) to the present day. It gives a voice to a people struggling to keep their identity in the face of terrible odds—a brutal occupation by Israel punctuated by daily violence and daily sorrow. The exhibition reveals with powerful clarity the Palestinian side of the story. What is at stake here is of tremendous importance. The lives as well as the traditions and culture of an entire indigenous population are in grave danger of being extinguished. Read more at Station Museum

More information about the show at StationMuseum.com

ARTISTS:

Zuhdi Al-Adawi

Tyseer Barakat

Rana Bishara

Rajie Cook

Mervat Essa

Ashraf Fawakhry

Samia Halaby

John Halaka

Rula Halawani

Mustafa Al Hallaj

Jawad Ibrahim

Noel Jabbour

Emily Jacir

Suleiman Mansour

Abdul Hay Mussalam

Abdel Rahmen Al Muzayen

Muhammad Rakouie

Mohammad Abu Sall

Nida Sinnokrot

Vera Tamari

Mary Tuma

Adnan Yahya

Hani Zurob

POETRY

Nathalie Handal

Mahmoud Darwish

Fadwa Tuqwan

"Made in Palestine" In the Press

- Kris Axtman. An artistic ‘road map’ to progress. The Christian Science Monitor. May 28, 2003. P22 http://www.csmonitor.com/2003/

0528/p02s02-ussc.html - Delinda C. Hanley. Made in Palestine”: A stirring art exhibit Rocks Houston and Hits the road. The Washington Report on Middle East Affirs. November 2003. P32

http://www.wrmea.com/archives/November_2003/0311032.html - Peter Applebome. Palestinians, Jews and the Art of Getting Bent Out of Shape

- New York Times. November 21 2004. P30

- Patricia Johnson. Stirring Exhibits’ Made in Palestine. The Houston Chronicle. May 17, 2003. P 10D.

- Kelly Klaasmeyer. Peace Through Art. ‘Made in Palestine Humanizes the Middle East Conflict. The Houston Press. July 31, 2003. P 40

- Jonathan Curiel. Unknown face of Palestinian art. San Francisco Chronicle. April 3, 2005

http://sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?file=/c/a/2005/04/ 03/ING74C1ATK1.DTL - Robert Avila. History in the waking. Bay Area Guardian. April 5, 2005

http://www.sfbg.com/39/28/art_art_made_in_palestine.html - Ramsay Short. Palestinian artists create facts on the ground in America. The Daily Star. April 5, 2005

http://www.dailystar.com.lb/article.asp?article_ID=13991& categ_ID=4&edition_id=10 - Onnesha Roychoudhuri. Made In Palestine. Mother Jones Magazine. May 11, 2005

http://www.motherjones.com/arts/feature/2005/05/ palestinian_art.html - Linda Isam Haddad. Palestine US exhibit stirs controversy. English Aljazeera. April 20, 2005

- http://english.aljazeera.net/

NR/exeres/CEA8B997-8674-47F8- B950-514FAF66EDAC.htm - Radio press on KQEDApril 12, 2005

http://www.kqed.org/programs/program-landing.jsp?progID= RD19

Review: "Made In Palestine" exhibit

Rob Eshelman, The Electronic Intifada, 12 April 2005

Artist: Mary Tuma. Title: Homes for the Disembodied, 2000. Media: 50 continuous yards of silk, 13’x25’.

In the summer of 2003, I traveled to Palestine to write some articles for a few left-wing publications and websites. Dividing my time between East Jerusalem, Ramallah, Nablus, Jenin, and a handful of small villages, I shared countless cigarettes and pots of tea or coffee, along with an occasional meal, with Palestinians who told me about life under Israeli occupation. The checkpoints, home demolitions, curfews, early morning or late night military incursions, which together were the expressions of Israel’s cruel presence in the areas west of the Jordan River, were a consistent topic of conversation.

One afternoon, wanting to get an idea of the affects of Israeli enclosure on the economy of Palestine, I visited a Ramallah-based company that produced household and cosmetic products. Standing outside the factory that day, one could see the outskirts of Jerusalem some distance beyond the remnants of dilapidated carnival rides that rose above the nearby roofs. Inside the factory, a company representative laid out for me the convoluted processes his business had to follow in order to export their products. I could barely understand the bureaucratic schema much less imagine adhering to its procedures.

Detail from “Los Explotadores”, a 1926 fresco by Mexican artist Diego Rivera.

Our meeting over, he handed me a selection of the company’s cosmetic products as a gift. “Look,” he said while pointing to a label on a package of facial mud “Made in Palestine!” Indeed, in bold, boxy typeface were printed those very words. Then, through a huge toothy grin, he told me that this label was illegal under the codes I had just been told about.

Made in Palestine. The prohibition of those words appearing on products cuts to the core of the Palestinian struggle - an Israeli occupation that attempts to thwart any assertion of a Palestinian history or identity. But the production of those goods, with their prohibited label intact, also shows the steadfastness and inexhaustibility of the Palestinian people in the face of those efforts.

This contest between occupation and self-determination, history and erasure also establishes the subject for the first contemporary exhibition of Palestinian artwork in the United States. Fittingly, and perhaps a bit defiantly, the show is titled Made In Palestine.

The exhibition — on display from April 7th through the 21st at the SomArts Cultural Center in San Francisco’s South of Market district — is a collection of works from twenty-three artists, most of whom currently reside in Palestine. Included in the exhibition are two-dimensional works on paper or canvas, photos and sculpture, as well as textile and video installations. Together, this array of mediums becomes the tool for very personal and compelling commentaries on Palestinian identity and struggle.

Detail of a 1910 abstract piece by David Burliuk, the “father of Russian Futurism”.

“The show,” says Samia Halaby, an emeritus Yale University professor of art and exhibition participant, “[highlights] the power of the Palestinian experience.” She says that although the content of the exhibition may be intensely political, it is conveyed through the unique experiences of the works’ authors and therefore also highlights “a very personal experience.” Halaby, who has written a book titled Liberation Art In Palestine, says there is a rich history of modern Palestinian art into which the exhibit taps.

Its earliest members where influenced by the Mexican mural art tradition and Russian Futurist style of the early 20th century. Their primarily two-dimensional paintings or drawings were often meant to communicate to an exclusively Arab or strictly Palestinian audience. The colors of the Palestinian flag were frequently prominent in their works as were symbols of the Palestinian liberation movement. More contemporary Palestinian artists, says Halaby, perhaps due to their Western upbringing or influences, are attempting to communicate to a wider viewer base and are constructing more installation or multi-media type forms. Visitors to the Made In Palestineexhibition will have the opportunity to view both approaches.

Among the latter group of artists is Mary Tuma, a North Carolina-based artist and academic. Her installation, Homes for the Disembodied, is constructed from 50 continuous yards of black translucent silk. According to Tuma, “the singularity of the form is meant to symbolize the interconnectedness [of Palestinian life].” Tuma has woven this fabric into five slender dresses that are then suspended from high above the gallery floor. She describes these forms as “providing the spirits [of deceased Palestinians] with a space to dwell.” Her piece is a powerful meditation on loss and remembrance.

Muhammad Rakouie taught himself how to draw with the materials he could acquire—crayon and cut pillowcase linen, while imprisoned in the notorious Ashkelan prison in Israel. Palestinian artists are prohibited from using the colors of their flag or making overt reference to their struggle for liberation and autonomy. The design elements within his smuggled paintings refer to Soviet abstraction and social realism. He risked great pain and additional punishment by creating these images, which stylize prison life and captivity. He now lives in a refugee camp in Damascus, Syria.

The works of Muhammad Rakouie and Zuhdi al Adawi offer up images of repression and resistance. Both have created colorful crayon on cloth compositions while imprisoned during the 1980’s. Each have included some of the elements of Palestine’s early artists described by Halaby: severed prison bars and broken chains, children and birds adorned with the colors of the Palestinian flag, and themes representing the devastation of Israel’s occupation.

A number of pieces address the reality of Israel’s foundation - its supposed transformation of an underutilized and sparsely populated desert into a blooming, modern state. Emily Jacir’s Memorial to 418 Palestinian Villages Which Were Destroyed, Depopulated, and Occupied by Israel in 1948 is a refugee tent adorned with the stenciled names of Palestinian villages uprooted during Al-Nakba (“The Catastrophe”), referring to the razing of Palestinian villages and dispossession of refugees around the time Israel was established in 1948.

In Father, artist Tyseer Barakat illustrates his father’s life through a series of images displayed within the drawers of an architectural cabinet. The viewer, by sliding open each of the draws, is presented with a different stage of his father’s story — home, diaspora, and exile. Here, these two artists reduce to mythology Israel’s process of “making the desert bloom.” Other works take on issues such as Palestinian’s relationship to land, Israeli military practices, and the incongruity of US and Arab news networks.

While imprisoned in Ashkelan prison, Zuhdi Al Adawi taught himself to make art. His expressionist drawings depict the psychological anguish and physical torture he endured there. He now lives in a refugee camp in Damascus, Syria.

Made In Palestine was originally organized by curators from the Station Museum in Houston, Texas and was shown in 2003. Since that time, the show has, sadly, been in storage and organizers from around the county have been attempting to raise funds and secure gallery space in order to tour the collection. Dozens of venues have been contacted, but organizers have received few responses.

“We’ve basically received a ‘no’ from everyone,” says Halaby, discussing efforts in New York City and other cities to secure exhibition space. In November of last year, a group in nearby West Chester County, New York organized a benefit to raise funds to have the exhibition in their community. A pair of county representatives went ballistic on hearing about the event and fired off an angry press release that characterized the Made In Palestine exhibit as “offensive art that glorifies terrorism” and “contained anti-American, anti-Israel and anti-Jewish hatred, as well as pays tribute to terrorists.” A state legislator described the exhibit as a “propaganda show for assassins.” The benefit went ahead as scheduled, but the incident exemplifies the impediments in having Made In Palestine displayed in cities across the country.

Getting the San Francisco show off the ground, however, has proven to be far less problematic. “It’s been a conspiracy of circumstances,” says Susan Green who has been central in orchestrating the SomArts exhibition. Since 1989, Green has been traveling to and organizing art projects in Palestine. On one of these trips last fall, she spoke with Barakat in Ramallah about Made In Palestine. She was fascinated by his description of the exhibition. Coincidentally, Green and a small group of other Bay Area artists had sought to curate a show of their own work about the occupation of Palestine: “So, we decided that if SomArts would agree to having [the Made in Palestine show] instead of our show we would then turn our attention to promoting the show and making it happen.”

The efforts of Green, along with those of the Justice in Palestinian Coalition, have meant that the San Francisco exhibition is the first time that Made in Palestine has been displayed since the original Houston show. A series of events will coincide with the exhibition throughout the month of April.

Samia Halaby

Made in Palestine is an extraordinary sampling of Palestinian art. There are many histories, many interpretations, and many reactions, both personal and political, to Israel’s occupation and to being Palestinian. While the Israeli state and crazed public officials on the home-front seem bent on limiting expressions of Palestinian identity, whether that be product labels or art exhibits, there continues to be those who challenge those enclosures. “This is not a culture that will go away with ease, ” says Samia Halaby describing Palestinian art and resistance, “it is an ancient culture that will assert itself again, again, and again.”

See you at the show.

Rob Eshelman is a San Francisco-based journalist. His articles have appeared in the San Francisco Bay Guradian, Brooklyn Rail, Counterpunch, and Clamor. He can be e-mailed at robeshelman@riseup.net.

Made in Palestine

— By Onnesha Roychoudhuri

Tue May. 10, 2005 11:00 PM PDT

Photos: Hickey-Robertson Photography

Is it possible to speak openly in America about the Palestinian plight? The reaction towards one art exhibit suggests not.

Notwithstanding the recently renewed peace efforts between Palestinian and Israeli leaders in the Middle East, it is still difficult to discuss the conflict openly here in the United States. It was only recently that Joseph Massad, a Palestinian-American professor at Columbia University, came under fire for being "anti-Israel." As it turned out, an ensuing investigation cleared Massad of all changes but one: the professor had become "angered at a question that he understood to countenance Israeli conduct of which he disapproved and… responded quite heatedly." Was Massad acting intemperately? Perhaps. But the larger issue here is that the question of Palestine has become so difficult to discuss, so thoroughly politicized, that anyone who acknowledges the existence and mistreatment of Palestinians is seen as either sanctioning terrorism, or being anti-Semitic, or both. So long as this view prevails, there will be no hope of any meaningful discussion of the conflict.

One person who recently got to see this chilling effect up close is James Harithas, an art curator in Houston. Harithas' gallery, the Station Museum, had displayed a Palestinian art show, "Made in Palestine" that opened in May of 2003. The exhibit contained work from a variety of Palestinian artists—from photos of "martyr billboards" in Gaza to ceramic olive trees—that was both deeply personal and inherently political. Originally, the exhibit was only supposed to run for three months, but Harithas extended this a further three months, into October, as it drew thousands of people from across Houston. One of the curator's closest friends, a Jewish man, came to see the exhibit. "I could see how hard it was for him," said Harithas, "But it really moved him. Now he's handing out the ['Made In Palestine' catalogue] to his relatives." Finally, after receiving some 20,000 visits to the museum, he felt it was time to move the exhibit to another city.

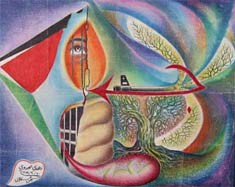

“Tale of a Tree,” by Vera Tamari.

That's when Harithas hit a wall. As he told al-Jazeerah, "I thought I had enough contacts to get this exhibit shown in museums across the nation, but I found out that even people who I considered close contacts said off-the-record they would lose their museum funding if they were to hold an exhibit that was pro-Palestinian." It is clear that "pro-Palestinian" has a negative connotation here in the United States. The implication is that the term denotes anti-Israelism, which is, in turn, a short hop away from anti-Semitism. Alternatively, "pro-Palestinian" implies "pro-terrorist." But it's important to note that nowhere does the "Made in Palestine" exhibit claim to be "pro-Palestinian," or to support terrorism, or to persuade people to become anti-Semites. It simply puts forth contemporary Palestinian art, the sort found in any other art exhibit, from images burnt in wood depicting the life of one artist's father, to family portraits, to photo negatives and ink drawings.

Nevertheless, after submitting the exhibit to ninety different museums, all Harithas had for his troubles was a file folder full of rejection slips. The San Jose Museum of Art had turned him down because some of the exhibit's work was "too polemical and might offend our audience." Two Westchester County legislators in New York issued a statement demanding that the County Executive prevent even a fundraiser for the exhibit from taking place. The statement accuses the exhibit of containing "several paintings, photos, and poems that demonstrate anti-American, anti-Israel, and anti-Jewish hatred."

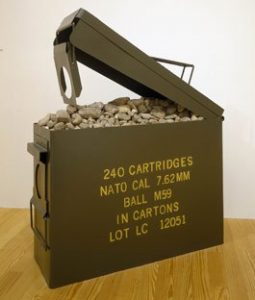

Adding to the various critiques of the exhibit, New York Assemblyman Ryan Karben protested the "displays of violence that the artists claim are showing the proud Arab masses standing up to advanced ammunition of the Israelis using only stones." The offending piece of art? An ammunition box that would normally hold bullets for M-16 rifles filled with rocks. And the artist never even made the claim that Karben attributed to him. According to the exhibit catalogue, the box in question was intended by the artist to communicate the "commentary on unfair fighting."

Finally, after two years of searching, the exhibit finally found a venue in San Francisco—in a small cultural center downtown. One of the few artists who could leave Gaza and the West Bank to attend the opening was Vera Tamari. An art teacher in Ramallah, Tamari seemed like the perfect person to provide insight into the Palestinian art movement. When I asked her what she intended to convey with her artwork—largely consisting of ceramics and relief work—she said very little about politics. Rather, she explained, her focus was simply to make the concept of "Palestinians" and "Palestine" visible to the public:

I think it's an important reflection that there is a people and that the people have a right to express themselves. They have issues that they want to tell the world, stories that they have to tell the world. Many of the works here are not directly political, but they are political in the sense that we want to tell the story of what's happening in Palestine. People ignore the fact that there are Palestinians who have the same potential as other people in the world, that Palestinians are like other people, that they can live, can produce art and music. [Read more here.]

“Father,” by Tyseer Barakat.

Even as I pushed her to explain the underlying political message of her art, Tamari kept pushing back to make the point that Palestinians were a real people and that the highest function of the art was to reveal that these people exist and have a culture. That simple statement was her politics. The fact that this reality is often obscured lies at the root of our inability to have a proper discussion about Palestine. In 1969, then-Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir told London's Sunday Times, "There is no such thing as a Palestinian people… It is not as if we came and threw them out and took their country. They didn't exist." Early Zionists coined the slogan, "A land without a people for a people without a land." Since then, Palestinians have struggled to assert that they do, in fact, exist; not just as martyrs and militants with a political agenda, but as a people with a culture that many would like to erase.

Even today, Harithas struggles to find American museums that will house the exhibit. It is possible that three more U.S. exhibits will come about; two of which will need to be funded with money the Palestinian artists have raised themselves, and one by a university. Meanwhile, the Mexican government has tentatively agreed to fund an exhibition in Mexico City, and there are rumors that it may find a venue in Australia. Harithas would like to see the sort of discussions he saw in Houston, open discussions about Israel and Palestine, take place in other U.S. cities. But it's not clear that this will happen anytime soon.